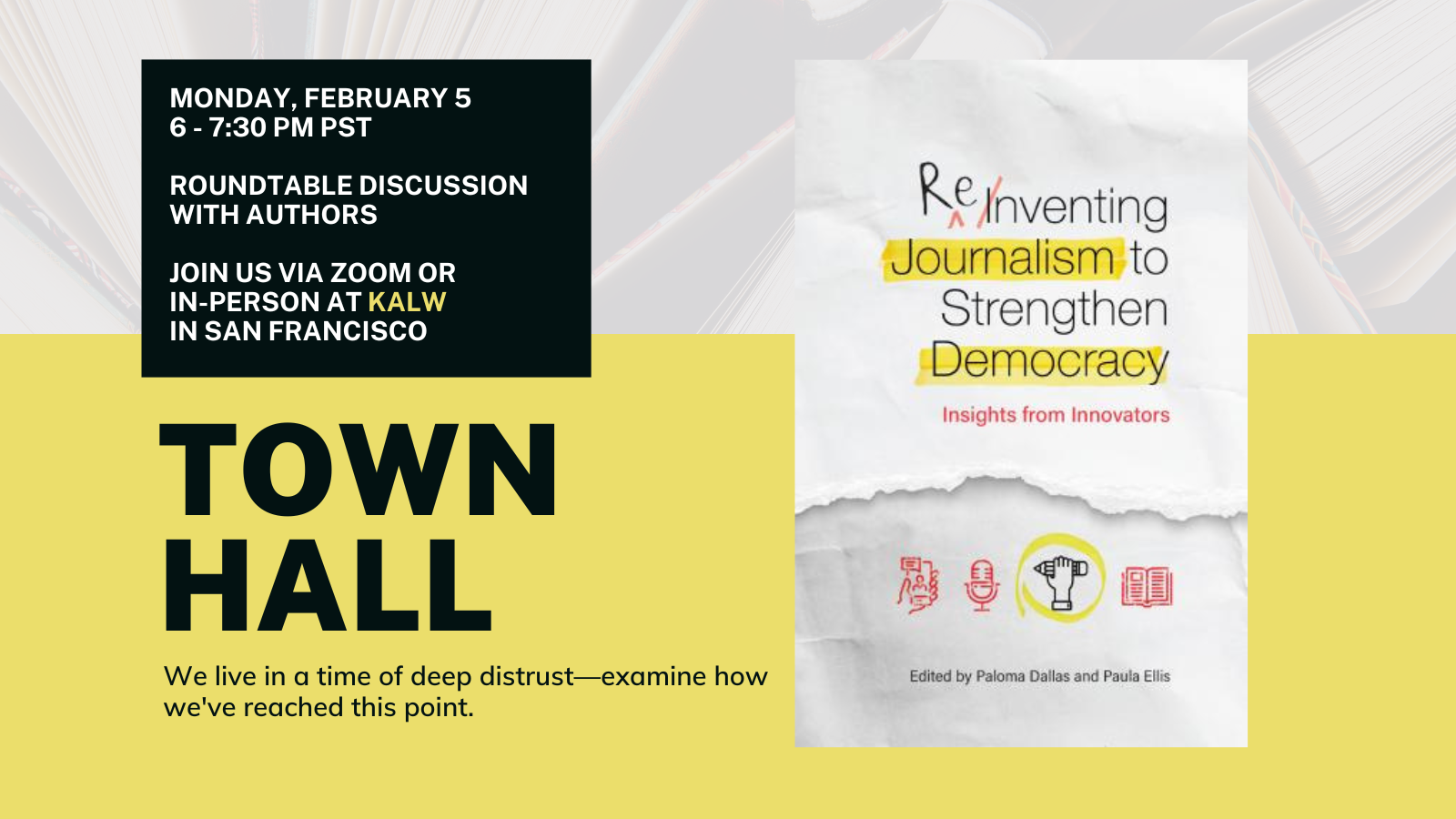

In 2023, the Kettering Foundation published a volume of essays on growing distrust of news media and opportunties for new practices to engage a diverse audience. Journalists from newspapers, public radio, civic media groups, and new media collectives contributed essays with their perspectives on how reinventing journalism as we know it can strengthen democracy. On February 5, 2024, KALW Public Media will host a free Town Hall, co-sponsored by the Society of Professional Journalists and the Kettering Foundation, featuring some of the authors, including Maynard Institute Co-Executive Director, Martin G. Reynolds. This blog includes an excerpt from his essay, titled “Dismantling Systemic Racism in News.”

From the publisher: During summer 2020, the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor sent shockwaves across America. Newsrooms and the journalists in them also felt the shock. Martin Reynolds, former managing editor and editor in chief of the Oakland Tribune and co-executive director of the Robert C. Maynard Institute for Journalism Education, was one of them. Even though Reynolds saw himself “in Floyd, in Taylor, and in the faces of countless other people of color who had been slain by police,” his initial instinct was to maintain his objectivity and to frame these events through the lens of a media professional and not a Black man with a Black son. Reynolds examines this experience and suggests some ways the dismantling of systemic racism in newsrooms might begin.

The following is an excerpt from Reinventing Journalism to Strengthen Democracy: Insights from Innovators, published by the Kettering Foundation in 2023 and edited by Paloma Dallas and Paula Ellis. With persmission, we are sharing an edited excerpt from the essay, “Dismantling Systemic Racism in News,” written by Maynard Institute for Journalism Education’s co-executive director Martin Reynolds.

Dismantling Systemic Racism in News

It feels difficult at this moment to return to the summer of George Floyd’s killing. I remember sitting in my car, rewatching the video on my phone, listening to accounts of protests. Hearing about Breonna Taylor and the list of other Black men and women and people of color killed by police was overwhelming.

I was enraged.

I was distraught.

I was scared.

I was ready to fight back.

How best to do that?

I decided I would never allow a police officer to press the life out of me. Trust in following police commands had been broken in a way I hadn’t before experienced. There was something about that time that felt profoundly different from other instances of police violence that I had helped cover or witnessed during my journalism career.

This time, tears of rage streamed down my face as I sat in my car.

Something snapped me out of a state of the journalistic objectivity that had guided my view of these stories and tragedies throughout my years as a journalist. This felt different and I could no longer separate my own Blackness and humanity from Floyd and from Taylor, slain in her own apartment by police following a no-knock warrant that was not issued for her.

For those reading this who aren’t journalists and who must be bewildered at how such separation from tragedy can be navigated, I must explain that I, among so many of my colleagues, was schooled in the objective approach to journalism.

I was taught that you kept your views on these issues from entering the coverage of a story, agreeing to a certain kind of internal invisibility. You are the witness, not the participant. You are the storyteller, not a character in the story.

I was instructed that who you are and what you have experienced have no place in the framing of a piece. You articulate what happened, with context of course. But often straight news stories about an incident weren’t the place for nuance and deep historical context. In the world of daily newspaper journalism where I was forging a career, you had to keep it moving.

“You can always do a folo (the journalistic term for a next-day story),” one of my former editors would say as she pounded out succinct edits on deadline.

News always happened the next day, so you moved on to the next homicide, fire, robbery, or carjacking. Or, perhaps the bit of context you did insert was removed or challenged by an editor or cut by the copy desk for space or because an editor thought it wasn’t appropriate.

I realize now that the invisibility extended beyond the role of journalist to a deeper place. I had to embrace the invisibility to survive, to find my place, to belong. But it wasn’t a true belonging.

Early in my career, I felt I had to compress elements of my identity and learn to turn away from the experiences that shaped my perception of the world. It wasn’t something that anyone necessarily said. It was more subtle and yet profound.

As that summer of violence and protest was unfolding, my initial instinct was to maintain my objectivity and to frame my view of these horrible events through the lens of a media professional and not a Black man with his own Black son.

Countless cases of Black and Brown people slain by police over the years hadn’t shaken that training, even though I felt pain each time it happened. The blatant racism on the part of police was something I had experienced many times, particularly as a young man, and I always felt as though it eroded my belief in democratic institutions.

The conflict of being a taxpayer and feeling under threat is a paradox I was never surprised by. I was taught that you kept your views on these issues from entering the coverage of a story, agreeing to a certain kind of internal invisibility.

And as news outlets scrambled to cover Floyd’s killing, something clearly snapped within them. The people who had so often been invisible were demanding to be seen. The reckoning in the streets, where we heard calls for racial justice, were echoed in newsrooms.

And there is a damn good reason for that. Fairly recently, newspapers, including the Orlando Sentinel, Los Angeles Times, Kansas City Star, Baltimore Sun, and the Philadelphia Inquirer, have, in various ways, admitted and apologized for their histories of racist coverage and the inflaming of racial tensions.

In a compelling Poynter Institute series, Mark I. Pinsky, author and former staff writer for the Orlando Sentinel wrote:

In recent years, a handful of the region’s newspapers have stepped forward to accept responsibility for biased reporting and editorials, shouldering their share of the burden of racist Southern history. They are acknowledging—belatedly—what their forebearers did and did not do in covering racism, White supremacy, terror and segregation over the past 150 years. Some newspapers, including the Sentinel, had especially grievous sins to confess.

The Inquirer’s look into its history, which was done by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Wesley Lowery, also apologized for the harm it had caused to Black journalists who worked for the paper, in addition to the Black community.

“The journalistic examination of the Inquirer by Wesley Lowery published this week [February 2022] puts our failings in brutal relief,” wrote Elizabeth H. Hughes, the paper’s publisher. “The reporting shows not only that we have not done right—it reveals, starkly, that we have done wrong. Black voices in the story—inside and outside the newsroom—articulate forcefully the harm we have inflicted over decades.”

As I reflect on this, now that some time has passed since the summer of Floyd and Taylor (which was followed by an insurrection fomented by a sitting president), I will say that my faith in democratic institutions does not have the luxury of being eroded by individuals not worthy of serving in them.

Looking at how representatives in the Trump administration, Congress, and even the spouse of a Supreme Court justice have behaved and perpetuated lies they know to be untrue has in some strange way evolved my view of the importance of these flawed but vital institutions.

Either the institutions themselves must be dismantled and rebuilt from the ground up or individuals with honor and integrity must stand up and lean against the pillars of these institutions and offer support to their cracking foundations.

I must admit that I am not sure which of these makes the most sense, or if either makes any sense.

The questions for me remain, What will be the true impact of these apologies? You can’t change an institution if the majority of the people inside it are unable, unwilling, or don’t know how, to unwind decades of socialized racism and bias. It is that racism and bias that have left so many feeling invisible, like they don’t belong in the very profession they have worked so hard to join.

I have to admit I never expected to “belong” in my newsroom. I was taught to endure, by journalists of color who were older and wiser. There wasn’t anything close to the refreshing expectation of “cultural competence” on the part of the institution that some younger millennials and Gen Zs have now come to call for.

I am glad they are, but that was not the reality I stepped into. The preparation I received was in the form of encouragement to sustain; to expect the arrows, the lack of cultural humility, blatant ignorance, and tone deafness; and to push through it in service of my career and

the need for more journalists of color in the newsroom.

We were prepared by journalists of color who were boomers and who were shaped by the experiences of their times and who were steeped in the civil rights movement. I was taught to understand that, in many ways, my presence was a form of protest.